Veins of Inspiration

Some thoughts on the Stancills clay mine exhibit,

Coming Home: A Journey in Clay

Stancills Inc. has been a family owned mining and manufacturing business since 1934. They mine sand, gravel, and clay for industrial use and make custom mixes for sports field construction, the geo-technical industry, and horticulture. Over the years Terry Stancill and his daughter Emlyn have cultivated friendships with artists enthralled with the beauty of the mine and the quality of the clay. They decided to create a gallery exhibition directly into the earth in conjunction with the 2005 NCECA conference in Baltimore.

Torso Catherine White

On a Thursday, the week before the exhibit was to begin, Margaret Boozer and I drove across the Susquehanna River on I-95, to Stancills, in Perryville, Maryland, to install fired pots and sculptures into the raw clay. The mine itself is an amazing place to see and feel especially for a potter. The elemental quality of the material is inspiring, exuding a simultaneous relationship to the geology as well as to the inherent potential of artistic manipulation.

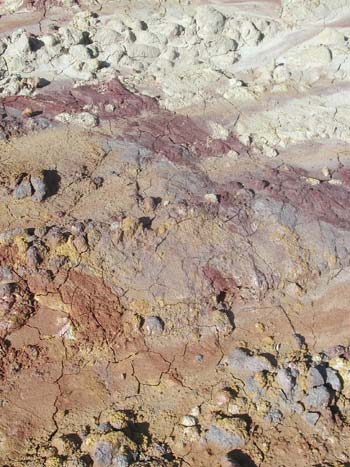

As we worked the frozen veins of clay, the fired work jumped out against the raw material ranging from white to red, gray, black, and purple. The drying, cracking, freezing, and plasticity of the clay drew pictures in my imagination. Here I was in the gentle, rolling geography of Maryland not far from the Chesapeake Bay, yet I felt as if I was standing in a remarkably wet New Mexico. As we chipped niches into the clay walls to prop our pots, I felt like a kid pretending to be an ancient pueblo cliff dweller. As we walked and experimented, the intimidating scale and rawness of the landscape transformed into feelings of inspiration whelming up from the endless and intricate colored clay striations.

Channel Margaret Boozer

In such a huge space there is room for Paul Chaleff’s one-ton sculpture to stand quietly grounded, as well as for Warren Frederick’s rice bowl, set in a carved niche, to surprise the viewer with its serene, wobbly shape. Margaret Boozer’s “Channel” drawing is placed high on the face of the clay cut; the interplay of the dripping slip against the drainage of the earth’s raw face viscerally resurrecting the point of her departure. Placed by the pond in a more gentle and reflective part of the exhibition, Willi Singleton’s large jars stand like sentinel lions at the entrance of a temple. Carolyn Bernstein’s installation is reminiscent of hollow bones as they embrace a swatch of grasses alongside the entrance path, the red surface wash reflecting the color of a distant red outcropping.

There is a mysterious blend of ancient forces--those that created the clay, gravel, and sand--with the modern, human strengths (and failings) of the machinery used to move, manipulate, and fire clay. Tensions are created between the sight of the fired object contrasted against the raw material. Glazed and unglazed presences stand side-by-side conversing eloquently about the role of human touch. Fired containers and sculptural found-objects both seem to speak in the presence of their origins in this industrially manipulated yet somehow natural outdoor site. We see nature refracted through the artist’s focus, the choices of found objects juxtaposed with the intentional alterations of the maker.

As artists we can tightly control clay and play by its physical rules or we can attend to each shift in the process, amplifying aspects of unpredictability and chance through clay’s transformative passage from excavation to wet forming, drying, and firing. Walking on the rough earth path one can almost inhale Stancills clay, encountering how other artists breathe, each choosing a dialect of clay to create distinct and remarkable poems.